Foreshadowing vs. Telegraphing

Much like the common writing advice “Show, don’t tell,” one is implicit, the other explicit. It’s the food for thought, not the thoughts themselves. Both are methods in writing that communicate to the reader of something that is to come. Here is an example of telegraphing:

I will provide my opinion on telegraphing. I’m not much a fan of telegraphing as it tends to kill the impact of a thing before it happens, and it tends to be redundant.

Voila, I telegraphed my opinion on telegraphing. In my example, the sentence referencing what was to come can be discarded and nothing of value would be lost. There are, of course, examples in which telegraphing can be worthwhile. Another example of telegraphing from the film Cloud Atlas:

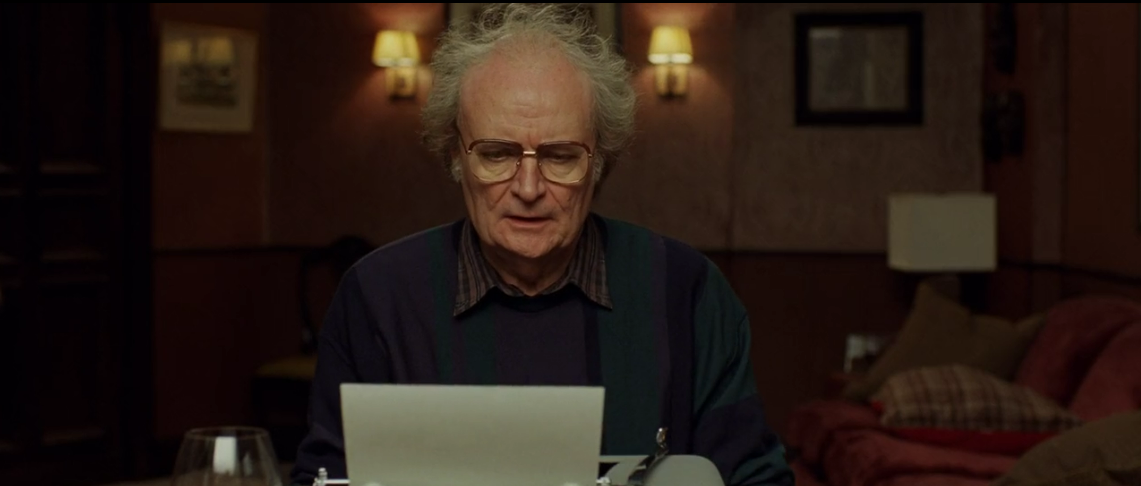

“While my extensive experience as an editor has led me to a disdain for flashbacks and flash forwards and all such tricksy gimmicks I believe that if you, dear Reader, can extend your patience for just a moment, you will find that there is a Method to this tale of Madness.”

For those who have not seen the film, Cloud Atlas involves a plethora of flashbacks and flash forwards and “all such tricksy gimmicks.” Here, the narrative as relayed by the character Timothy Cavendish is both a message told in character as well as a message told to the audience letting them know what to expect.

Now, to take another example from Cloud Atlas but this time to demonstrate foreshadowing: in the film’s opening one of the protagonists is introduced to the character Dr. Henry Goose who is avidly digging on a pacific beach in search of teeth discarded by cannibals for the purpose of selling them for money. This says much about his character, and it may not come as a surprise that he later betrays the protagonist in an effort to gain more money, but also amidst his betrayal he says, “The weak are meat, and the strong do eat.” That’s a pretty clever connection. Though the film somewhat watered down the character to be driven by greed, as in the book the purpose of getting the teeth was for the character to get his own revenge for a matter which serves as another layer of irony, both do well in eliciting an idea for what to expect or pay attention to later on without explicitly saying what would happen.

Both foreshadowing and telegraphing have a time and place to be used. Both can work and not work depending on the circumstances. I previously gave an example of how telegraphing didn’t work followed up by how it did; the way it worked (for me) is that it spared the audience from spoiling something significant. In a sense, this is pretty similar to foreshadowing. While it explicitly told the audience about flashbacks and whatnot, it didn’t explicitly say why or what they were for. Another way the Cloud Atlas example of telegraphing worked (for me) was that it wasn’t strictly meta. It was also insight into the mind and commentary of the character of Timothy Cavendish giving some sort of foreword for Dermot “Duster” Hoggins’ book Knuckle Sandwich. As another example of foreshadowing, the heavily implied violence of the book title and Dermot’s character foreshadow the troubles Timothy faces later in the story. So, basically, telegraphing works best (for me) when it’s sparing with what it tells the audience, and when it’s internally relevant to the story. Some other ways it might work but are less effective (for me) are when it’s used as a narrative device (e.g., it sets a tone, it affects the pacing).

It’s hard to think of an example of when foreshadowing doesn’t work (for me) because it could be a case of a mistaken hint or something so tenuous that it is completely overlooked (e.g., “The curtains were blue”). On the other end of the spectrum, something could be so obnoxiously hinted that it’s too obvious to amount to a payoff (e.g., “Don’t trust anyone!” and the character who says that turns out to be dishonest). There are great examples of obvious foreshadowing that work, like in any of Edgar Wright’s Cornetto trilogy (e.g., “He’ll be in bits tomorrow!” from Hot Fuzz, the entire opening of The World’s End). Tight narratives that follow the principle of Chekhov’s gun in which every element of a story is relevant to the plot can be extremely compelling, but can also fail due to the audience being conditioned to know everything is mentioned for a reason. Tangential, this is a reason I enjoy fantasy stories: not everything is mentioned to be relevant to the plot, it can be mentioned for leisure and/or the sake of world-building. There is, of course, a limit to what is entertaining and what is gratuitous in being described.

Well, that’s about all I have to say about foreshadowing and telegraphing. I will now stop talking about foreshadowing and telegraphing.